News & Updates

Webinar Summary: IMF and (bread) riots: Perspectives from Tunisia | ملخّص الندوة: صندوق النقد الدولي والانتفاضات (انتفاضات الخبز): وجهات نظر من تونس

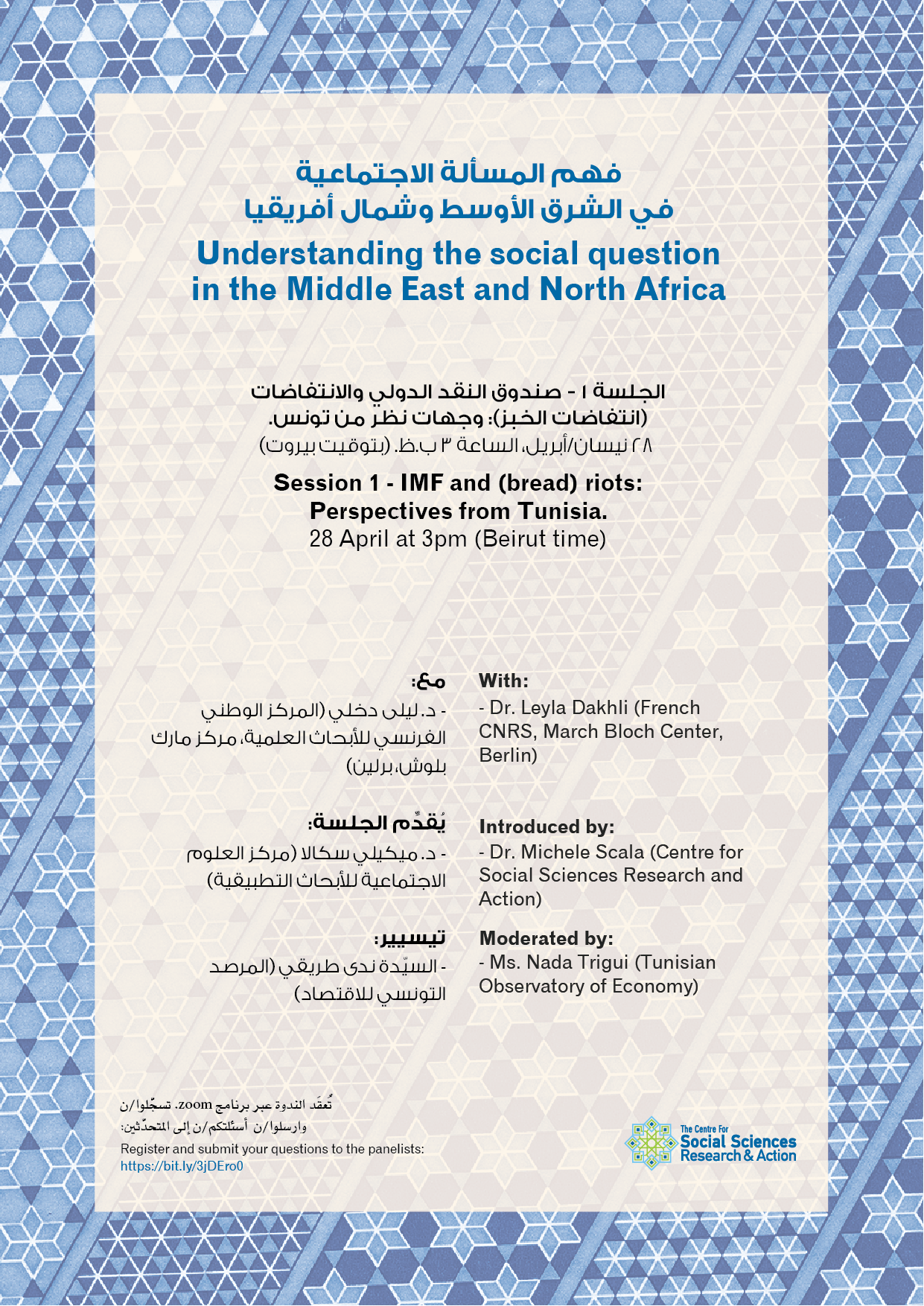

“IMF and (bread) riots. Perspectives from Tunisia” was held on Thursday 28, April 2022 as part of our centre’s webinar cycle “Understanding the social question in the Middle East and North Africa”.

The discussion, introduced by Dr Michele Scala (CeSSRA) and moderated by Nada Trigui (Tunisian Observatory of Economy), featured an intervention given by Dr. Leyla Dakhli (CNRS, March Bloch – Berlin).

Leyla Dakhli presented her published research which examines the social revolts that broke out following the implementation of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) in Africa and the Middle East starting in the 70s. She focused on the case of the so-called “bread riots” that took place in Tunisia during the winter of 1983-1984, drawing from her article: “The Fair Value of Bread: Tunisia, 28 December 1983–6 January 1984”. International Review of Social History, 66 (S29), 2021, 41-68. (accessible here).

As Leyla Dakhli explains, the riots erupted around – at first glance – material demands linked to the removal of subsidies on basic items and the subsequent price hike that struck pauperised populations’ subsistence strategies. However, far from constituting “bread and butter revolts”, the so-called bread riots of 1983-1984 expressed the deterioration of a broader social contract in which the state was supposed to guarantee “the fair value of bread” in a context of social and economic distress linked to the implementation of neoliberal reforms. What mobilised the lowest swathes of the population was not, or was less, the fact that bread became (more) expensive. People were asking for “fair” prices and “talking about fair prices is talking about social justice”, as stressed by Leyla Dakhli. In this context, “fair” means a fair redistribution of wealth and, more specifically, a fair “compensation for the work [people] were doing”. It was about “what people felt they were giving with their work and what they were getting back” from the decision makers.

As discussed by Nada Trigui, Leyla Dakhli’s work sheds light on the actors behind the so-called “bread riots”, allowing to re-embed the latter into a longer and still unfolding historiography of struggles for “social justice” and “dignity” in Tunisia and throughout the region. It also bridges past and present issues involving the relationship between International Financial Institutions (IFIs) and Tunisia. As Leyla Dakhli’s work points out, the reduction of the subsidies on wheat products in the 80s was perceived as a breach to the “authoritarian social compact” that maintained a certain balance for the most vulnerable.

The recent reduction of fuel subsidies – imposed on Tunisians during the general lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic – similarly sanctions the most vulnerable and will most likely drive the poverty rate up by 3.6% (according to a 2017 report). In line with neoliberal policies, the suppression of universal redistribution mechanisms such as food or fuel subsidies was (in the 80s), and is (nowadays), justified by both the authorities and the IFIs over their regressive and inequitable nature. What is seldomly pointed out is that the removal of subsidies also has an inequitable outcome over low, middle, and upper classes. Or, as Leyla Dakhli frames it, that “the price of bread is not the same for everybody anyway”. In this perspective, the removal of compensation mechanisms also undermines the inclusivity of an already fragile social contract, further pushing to the margins the most vulnerable populations.

The pursuit of neoliberal policies, both in the 80s and nowadays, reinforce the divides between “those who can “be part of it” [social contract] and those who remain on the side-lines, who build other registers of belonging, other systems of recognition…”

In this framework, the election of Kais Saied and, later on, the support he received to his July 25 “coup de force” could be read as an attempt, by large swathes of the society, to find a new form of recognition that the “democratic transition elites” failed to bring.

The webinar recording is now available and openly accessible on CeSSRA’s youtube channel here.